It is nearly impossible to participate in today’s society without sharing some of who you are with someone you don’t know. We used to dole out our personal information in drips, mostly to those who were close to us. As our tools for managing personal information (including facts previously considered private) improved, we started making deals for our data.

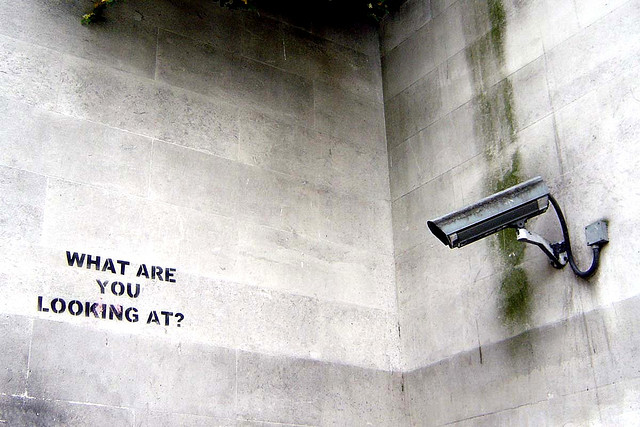

Marketers promised to pony up good money for our locations and our buying behavior (and more), and we said OK! Now, every click, every like, every share, every post, every shopping cart (full or abandoned), every heartbeat is tracked by someone, somewhere. Usually, now, that tracker is a faceless someone who is scooping up the data in order to understand us better and sell us more stuff.

On the other hand, we like all that stuff. We like our wearables and our Instagram pages, our Nest thermostats, our GPS, and our one-click Amazon Prime accounts. And we like having some minimal connection to those we know and love. Why not? Without really thinking about it, we’ve made a tradeoff giving away data for service, for easy connections and in a way that limits our out-of-pocket expenses.

The ease with which generally unwitting consumers make those data-for-access trades has been changing as personal data violations (via hacks or leaks) hit the news and we learn that the NSA has been sucking up more info than we thought. People’s privacy and security issues are going to be debated for years to come. This is territory is just now being explored. In a globally connected world, how can rules about something as nebulous and personal as notions of privacy be agreed upon by so many different economies, technology platforms and cultures?

The reality is that the train has already left the station. Big data is its own currency, and it’s also big business. For many companies trying to compete in global marketplaces, the advantages of technology and data-enhanced products are a must-have. However, consumers are becoming more aware of potential for identity theft and discrimination associated with sharing their data. I’ll leave the long-term legal and ethical arguments to others, and instead focus how to make this uneasy bargain work in the meantime.

What follow are three guidelines that marketers can hew to in order to be on the right side of this issue, and to maintain consumer trust and goodwill. They’re guidelines for business and for ethics.

Convenient

If you want my data, make the interaction simple and deliver something back to me that is personalized and demonstrably makes my life easier or better.

Example: The Disney Magic Band — With admission and some information this Radio Frequency wristband unlocks your Disney hotel room, allows you to buy food and merchandise at theme parks and gives you FastPass access to activities at the resort. Make no mistake, they are following you around the facility. But for many, the convenience outweighs the tracking.

Example: Tesco learned that travelers dreaded coming back from a trip and facing an empty fridge. They built interactive touch-screen kiosks that encourage travelers to shop while they’re waiting for their flight. The goods get delivered when travelers arrive home fulfilling on Tesco’s tagline “come home to a full fridge,” making busy people’s lives easier.

Relevant

Targeted and relevant applications of data are key to cut through the clutter with customers. They have to be focused and rare enough, though, that they sidestep a Big Brother creepiness. The clearest example here is on Facebook. A simple question like “Where did you go to high school?” seems simple enough, but it gets the user connected to more people and builds community that users find valuable. The user gets something that’s hard to find with such ease elsewhere for the low cost of one tidbit of information.

Example: MasterCard — They’ve recently announced a new program to geo-target consumers with Priceless surprises. The program could send you free upgrades while you’re waiting for a flight or award memorabilia as you attend a sporting event.

Example: Johnnie Walker Blue — A recently launched Johnnie Walker Blue campaign uses NFC on its bottles to interact with smartphones and deliver promotional offers, recipes or branded content for the life of the bottle—from the store shelf to the recycling bin.

Controlled

A recent study from Microsoft reports that consumer attitudes toward privacy is becoming more sophisticated as this deal-making process evolves. For instance, 57 percent of people want to be able to control how long their information stays online, a trend Microsoft calls “Right to My Identity.” This desire suggests an opportunity for marketers to offer easy-to-use control panels or dashboards to customize what is shown publicly or privately, or not collected at all.

At the same time, consumers are learning to be wary of the fine print, and they are getting support from the White House. In late February, a Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights Act was proposed. Consumers want more control to ensure secure, private interaction. This means marketers need to carefully structure the scope of their data creep as consumers become more comfortable with taking matters into their own hands.

Example: As if there weren’t enough to worry. Drones, equipped with cameras and widely available, are now one more technology that can invade privacy. NoFlyZone has created a voluntary no fly zone campaign enlisting manufacturers to program the drones to avoid areas designated on the list. Hard to know how reliable this would be but it demonstrates the increasing list of privacy concerns any citizen may face.

Example: Whether the goal is personal or enterprise protection Blackphone is designed to keep any sort of snoop out of your communication. It’s built with a custom-designed Android operating system combined with a suite of apps, and only one thing in mind — privacy. It’s inevitable: Individuals or companies in highly sensitive businesses will be investing in these tools to safeguard information, activities, and IP.

Though there is a lot of support for security, this too will generate debate. What matters to consumers is that businesses and governments that want information seek it in an honest, transparent manner.